It’s no secret that film noir is my favorite genre, and it’s similarly no secret that it’s an extremely male dominated one. Part of that is a function of the times- it was cooler to be sexist in the 40s and 50s when most noir came out*- but mostly it’s got more to do with the fact that most writers in the genre are male, and most writers write what they know (being male). There are exceptions to both those points, though not enough to either.

*Nobody agrees exactly what does or doesn't count as noir. If you don't like my loose definition, that's fine, but it's on you to mentally insert "neo" in front of it every time I mention it in relation to anything from after 1955.

If you’ve read my last few books, it’s pretty obvious that I think noir works just fine- if not better- with female protagonists. So, lacking a better idea for a deeper/more inspired article today, I did what all internet hacks do when they’re out of ideas: I made a list of some of the great noir leading ladies who do exist. Enjoy.

*Note: This is a list of primary protagonists only; there are hundreds if not thousands of great female noir love interests, femme fatales, or outright villains, but that’s another conversation entirely. Shout out, though, to Lizabeth Scott in Too Late For Tears, playing the protagonist, the villain, and the femme fatale all in one character. Ditto Linda Fiorentino in The Last Seduction.

5: Corky, Bound

"For me, stealing's always been a lot like sex. Two people who want the same thing: they get in a room, they talk about it. They start to plan. It's kind of like flirting. It's kind of like... foreplay, 'cause the more they talk about it, the wetter they get. The only difference is, I can fuck someone I've just met. But to steal? I need to know someone like I know myself."

The forgotten Wachowski movie, Bound is actually my favorite of their films. It’s a simple, classic noir premise- ex-con gets out of jail, meets a dangerous lady who’s already spoken for, people die*. The riff is that our ex-con is a woman, played here by Gina Gershon in probably her career-best performance. The dangerous lady is Jennifer Tilly, having the time of her life vamping through the scenery as Violet, and the third player is a surprisingly sympathetic (initially) monster played by Joe Pantoliano. I don’t wanna spend too much time on the movie as a whole- it’s got enough going on to warrant its own article and I haven’t seen it that recently- but I would say that it’s worth your time both as a great modern noir, and as a very tight, character driven thriller that strikes a stark contrast to the Wachowski’s later, louder, and frequently bloated work.

*Speaking of Lizabeth Scott, she’s in two classic examples of this formula: The Strange Love of Martha Ivers and I Walk Alone.

That all said, we’re here to talk about Corky. Here’s an early scene:

She’s a familiar type, right? Tough, competent, instantly aware of temptation and almost as instantly aware that she’s not quite strong enough to totally ignore it; note the wry smolder she's got going almost from the jump. It’s no spoiler to tell you it’s not long after that scene that “reformed” Corky is back to taking big criminal risks, and like Walter Neff (Double Indemnity) or Michael O’Hara (Lady from Shanghai) it’s not quite clear, even to her, whether she’s doing it for love, lust, or money.

Corky’s not reinventing the wheel here; she’s a classic noir antihero with all the same vices and virtues we’ve come to expect from the archetype, from poor impulse control to fierce independence to questionable taste in women. The Wachowskis smartly don’t bang the “hey, look she’s a lady!” drum (though the villain isn’t thrilled about being potentially cuckolded by a woman, but he’s a villain so fuck him), instead focusing on simply telling a story about a character. It’s a pretty damned good story- and a great character- and it’s a shame it took until 1996 for somebody to tell it.

4: Veronica Mars, Veronica Mars

"A teenaged private eye. Trust me. I know how dumb that sounds."

Probably the most predictable appearance on this list, Veronica’s a personal favorite (to the point that I partially dedicated Hungover & Handcuffed to her), and with good reason. Creator Rob Thomas has often claimed that Veronica Mars is a gender-flipped film noir, and it often is, but Veronica herself isn’t totally true to that formula. The closest thing to the classic hardboiled detective in the series is her father Keith; while Veronica’s inherited the snark and the detective skills, she’s also a much more hopeful, quixotic character than that trope usually allows for, combining elements of the more traditionally upbeat Nancy Drew style plucky girl detectives with the gritty toughness required by the genre.

Don’t get me wrong, Veronica’s by no means a soft touch. Especially in later seasons, she’s brutally cutthroat, frequently callous, and clever in a very sinister way; it’s not hard to imagine a story where her particular brand of cunning makes her the villain... and there are characters in her story that would argue she already is.

Still, though, it’s the warmth she’s able to maintain in her personal relationships that sets her apart from most noir detectives; Sam Spade is a lonely man who banters with his secretary, hates his partner, and despises the woman he’s having an affair with. Veronica, on the other hand, spends most of her off-time palling around with her support staff (namely Mac and Wallace), loves her father, and has half a dozen close friends she’d die for- and she frequently risks doing exactly that. She’s the rare noir protagonist who’s able to do the job without sacrificing too much of her humanity- though she certainly coughs up most of her innocence over the course of the first season- and it makes her a lot more compelling, and a much more well-drawn character, than she’d be if she were just “Spade, but female and also in high school.”

For all her trauma, Veronica’s able to hang onto enough of her idealism and heart that when we see her ten years later in the movie, she hasn’t become Spade or Marlowe or some of the other women I’m gonna talk about on this list; she’s still got friends, she’s in a healthy-ish relationship, and she doesn’t even have the traditional PI’s drinking problem. She’s not weaker for the absence, either; she’s still got Spade’s rigid moral compass, Marlowe’s wry cynicism, and the self-destructive tenacity of certain lesser sleuths in the genre (*cough*Mina Davis*cough*). She’s just also got enough strength of character not to let them haunt her to the extent her peers do.

Ultimately, Veronica Mars is so strong as a character that she defies the conventional miseries and vices of the genre, and it feels totally earned… mostly because she earns it.

Veronica Mars is currently streaming on Amazon Prime.

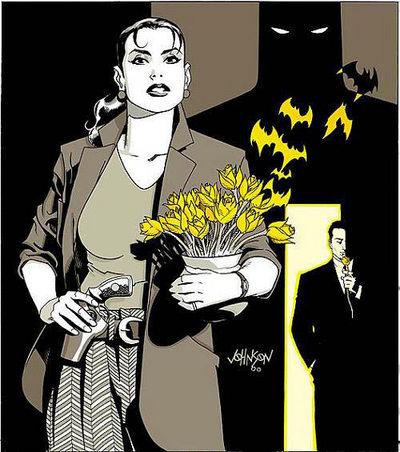

3: Renee Montoya, Batman the Animated Series, Gotham Central, Detective Comics, 52

"They've all got it easy. The supers and the wonders and the villains. All of them. They don't live in the grays. It's all black and white for them."

Our second LGBT heroine on the list, Montoya’s a hard character to summarize quickly; she started off as a minor supporting player on the 90s Batman cartoon, developed a following, migrated to the comics, graduated to a leading role, and eventually even become a superhero in her own right. Over the course of that journey, she went from mostly-functional adult to alcoholic womanizer to something much more interesting than either; her nature as a serialized character with so many writers’ finger-prints on her makes her tricky to compartmentalize.

So, we’ll focus on her most noiry era, from about No Man’s Land (an underrated classic Batman story) through 52 (a properly rated classic Montoya story), not least because No Man’s Land was when I really got invested in Montoya as a character. The elevator pitch for No Man’s Land is this: the US Government finally gets sick of Gotham’s shit, blows the bridges, and declares it a DMZ. Pretty much instantly, the city’s various criminals start carving it up in a massive anarchic gangwar. Oh, and Batman’s not there.

Montoya is, though, as part of a small contingent of cops led by Commissioner Gordon who stay behind to try and protect Gotham without any authority or backup, because it’s the right damn thing to do. She gets a great establishing character moment early on when, with some justifiable reservations, she bonds with and comforts Two-Face, ultimately steering him towards his better nature as Harvey Dent…for a while. There’s some great retroactive subtext here; we as readers wouldn’t find out till years later that Renee’s a closeted lesbian at war with her very Christian and traditional upbringing, but writer Greg Rucka (who wrote much of No Man’s Land and would later write the story that outed her) clearly already knew, and it makes a lot of sense that Renee would empathize both with Two-Face’s extreme identity crisis and his conflicting natures, and that Two-Face, in turn, would respond to what he’ probably consider a kindred spirit.

*catches self, successfully avoids writing 3,000 words about how awesome Two-Face can be under the right writers*

Anyways, it being Gotham, things deteriorate pretty quickly. Montoya ends up captured (along with Gordon) by Two-Face and features prominently in what’s probably the best Two-Face story ever (Jurisprudence). There’s a quiet moment at the end of that story that’s sneaky important for Montoya's long-term characterization, where Harvey Dent- in control for the moment- sadly turns himself over and Renee, in spite of everything up to that point, treats him with dignity, empathy, and respect.

Renee’s life goes pretty much to shit after No Man’s Land, as she’s outed against her will by Two-Face in what’s probably the worst Two-Face story ever (Half a Life) but a pretty great, and important, Renee Montoya story. The dominoes start falling there, and before too long she’s gone full noir-burnout, losing her job, her girl, and her relationship with her family. She climbs into the bottle, and into bed with whatever floozy is conveniently nearby, and if that were the end of her arc, it’d be a pretty decent noir tragedy about a good woman crushed by a bad city… but it’s not.

In 52, Renee is soon sought out by one of the all-time great noir comic book leads, a crime-fighting philosopher with no face known as the Question (real name: Vic Sage). Sage drags Montoya kicking and screaming out of her funk, and leads her on a worldwide adventure that isn’t really the point. The two become friends, and Montoya quickly comes to empathize with the extremely broken- and yet, extremely courageous- Sage. Unfortunately, Montoya’s too good of a detective not to notice that Sage is dying, and she grapples with some pretty heady stuff in the face of losing her savior. It seems a setup for Montoya to go down even harder than before, but it goes another way.

When all is said and done, Montoya finds a new purpose, taking on the mantle of the Question. Once a brave hypocrite who could stare down the Joker but couldn’t be true to herself or function without the structure of her job (or Vic’s quest) or the emotional support of a lover (or Vic), Renee becomes a completely self-sufficient character fundamentally obsessed with finding the truth of things, completely at peace with her own identity… and yet, in the doing, becomes a hero without any identity at all (like Vic). A literal faceless detective- the absolute antithesis of the double-identitied mobster that was once the architect of her implosion.

Her story goes on, and never really gets any better than that, but that journey laid out above of a seeker who can’t find themself, a soft-hearted empath who can find good in a mass murderer but can’t forgive herself for who she is, who loses everything again and again, and then finds solace, strength, and salvation in becoming a literal symbol of nothingness? Of a good cop with secrets who sees hers life undone by them and becomes instead a vigilante consumed with truth? That’s a goddamn noir epic, and one of the greatest character arcs serialized comics have ever put together.

Montoya’s been marginalized and misused since those stories, but No Man’s Land, Gotham Central, and 52 are all available wherever fine comics are sold.

2: Alicia Huberman, Notorious

"There's nothing like a love song to give you a good laugh."

You’ve probably noticed by now that, despite this being ostensibly a list about a genre most associated with the 1940s, the first three entries are all characters created after 1995. Unfortunate nature of the beast (most writers are men, remember, even including the creators of most of the women on this list), but there is at least one truly to shelf noir heroine from the golden age: Ingrid Bergman’s Alicia Huberman.

Strong-armed into infiltrating the home and heart of a suspected Nazi, Huberman spends most of the movie being callously used and manipulated by her would-be love interest and handler (Cary Grant) and obsessed over by her mark (Claude Rains). A case could be made that Grant’s the main character of this film, and he probably got top billing, but the meat of the plot, and the meat of the character work, falls to Bergman.

Repeatedly forced to sell out her own values, wants, and morality in pursuit of the greater good, Huberman’s bravery very nearly gets her killed. A more pretentious writer than I could make a case that she serves as a decent metaphor for the plight of women in noir in general, caught between a square-jawed hero and a monstrous villain, doomed to be desired by both but respected by neither. Metaphor or no, it’s where Huberman finds herself, and it’s where Bergman does her best work.

There’s a very specific nobility in a betrayed woman dutifully going through with her own betrayal because it’s the right thing to do- even though she knows both that she won’t be vindicated by it, and that it’ll likely get her killed. She may be wrong about one or both of those, but that’s not the point; the point is that heroism in the face of inevitable doom, moral hypocrisy, and a manipulative lover is the fundamental nature of most of the great noir heroes*. Bergman’s Alicia Huberman more than earns her place among them.

That she’s one of the only women of the era who does is a shame. That we at least got her is a minor miracle.

*This is an oversimplification. Spade and Marlowe inhabit a different corner of noir heroism, for instance, and many if not most noirs have no heroes at all. That said, a lot of the best ones are built from this same DNA; Out of the Past, D.O.A., Dark Passage, etc.

Notorious is available on YouTube or on Netflix’s DVD service.

1: Jessica Jones, Jessica Jones

"God didn't do this. The Devil did. And I'm going to find him."

Another really predictable pick, but she’s predictable for a reason. Jessica’s also kinda a problematic case, because her original incarnation by Brian Michael Bendis, while it certainly has its moments, ultimately ends up as nearly the antithesis of a good female noir hero. Bendis’ Jones winds up sidelined in the traditional gender role of “hero’s wife,” and loses most of her characterization- and most of what makes her great- in the process. Even in her first (and best) comic, Alias, Jessica’s a tough sell for a feminist audience, with an awful lot of time in the story devoted to her man-troubles, no memorable female villains, and only one particularly significant female supporting character (Carol) who spends almost all of her time talking about Jessica’s man-troubles. Her archenemy, the living personification of rape-as-drama known as the Purple Man, is defeated mostly by deus ex machine (the X-Men just made her immune to his powers) as opposed to anything Jessica really accomplished as the protagonist. Though she does apprehend him, his real comeuppance is saved for a later story, where he’s beaten half to death by Jessica’s husband. So… there’s that.

But I’m not talking about comic book Jessica. I’m talking about the whiskey-swilling, ass-kicking, absolute queen of all badass Netflix Jessica. Krysten Ritter and Melissa Rosenberg take Jessica where she always should have been, a self-driven trainwreck of a human being who’s messy, broken, scared, damaged and completely heroic in spite of herself.

Jessica’s got all the classic noir detective tropes handy- she’s got a drinking problem, a lawyer friend who gives her work, and a friendly but contentious relationship with the cops. She sleeps in her office, keeps to herself, etc. etc. But unlike Spade, Marlowe, and the rest of their classic ilk, she’s also got a hell of a past. Yes, there’s still all the trauma with Killgrave, and that’s an important part of who she is and how broken she seems, but there’s also the extensively developed sisterhood with Trish, and the fractious upbringing at the hands of Trish’s mother. Jessica came from somewhere; Marlowe and Spade, for all their greatness*, really didn’t. They were born with coats and fedoras on their tiny baby bodies, and one-liners on their mewling newborn lips. Jessica, though, she grew up, fought with her sister, dated the wrong guy… Jessica lived a real life before we ever got to meet her.

*For the record, this isn’t a criticism; Marlowe may be my very favorite fictional character, and Spade’s the prototypical and most famous noir detective for a reason. Both are great. Jessica’s just great for different reasons than they are.

When we do meet her, then, she’s a fully formed character in a way most protagonists- even outside this list or this genre- aren’t, at least not right away. She doesn’t have a tragic flaw, she has dozens. She doesn’t have one complex relationship we’re playing catch-up with, she’s got five. She’s not learning how to do her job or deal with her damage, she’s settled into a routine with both. Watching her forced out of that routine on both fronts- and into the role of heroine- is a big part of the fun, but that she starts in such an earned, established rut is what lets everything that comes later work so well.

In stark contrast to her four-color self, Netflix Jessica’s most important relationship isn’t Killgrave or Luke; it’s Trish. That’s the relationship with the most context, the most complexity, and consequently the most screentime. Killgrave’s her villain and Luke’s a love-interest, but Trish is the emotional heart of the story, and I don’t know that I’ve ever seen a noir story built around a non-sexual two girl dynamic like that. I’d certainly like to see more.

I’m realizing now that Jessica’s probably an article unto herself at some point in the future, so for now I’ll just sum up: if you’re looking for a morally complex, whiskey-swilling, broken-on-the-inside-tough-as-nails-on-the-outside, noir to her very goddamn bones protagonist, you’re gonna have a hard time finding anybody who fits the bill better than Jessica Jones.

You know, unless you read…

Honorable Mention/Cheap Plug: Mina Davis, Get Tough, Hungover & Handcuffed, Asshole Yakuza Boyfriend

"The worst part of being a pessimist is that you’re almost always right.""

Couldn’t help myself. I’m not going to pretend that Mina’s earned a spot on the same list as the rest of these ladies just yet, but it’s my blog, so she gets a paragraph or three. She’s less outwardly heroic than the women listed above, or at least she thinks she is, and she draws her motivation less from righteousness or nobility than from spite, guilt, and her need to fill her bottomless pit of a liver. Still, Mina’s usually on the right side of things, and much as she’d hate to admit it she’s ultimately one of the good guys when the chips are down… mostly.

She’s not as clever as Veronica, as competent as Corky, as strong as Jessica, as enlightened as Renee, or anywhere near as noble as Alicia, but she’s doing her best. She gets by mostly on toughness, stubbornness, and the Indiana Jones approach to problem solving. She collects personality defects like Pokemon, and she pushes people away with more fervor and less justification than even Jessica Jones, but being that broken makes her uniquely qualified to deal with the kind of monstrous antagonists some sick fuck keeps throwing her way*.

*Oops.

She’s got dubious taste in both men and women, but great taste in whiskey- meaning mostly that she thinks whiskey tastes great.

If that drunken, pessimistic, Korean-American gumshoe sounds like your kind of party, you can read some of her short stories here, her first novel here, or her (condensed) origin story here. Her next adventure is coming later this year; if you want to read that, too, I recommend signing up for the mailing list below this article.

This list is over, but it’s by no means complete. There are dozens of women I left off it, many of whom I’ve probably never even heard of. Do me a favor, please, and recommend them in the comments.